Revealing the flaws of thinking: An Exploration of “Thinking Fast and Slow”

Hey people,

were you ever looking for a bible, but regarding psychology? About the human mind and how it affects our decision-making, judgment, and reasoning? Well, I got the perfect fit for you, it's “Thinking Fast and Slow”, a fantastic best-selling book by the Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman. And boy do I have to say, this was the longest, excruciatingly fascinating book I have read so far.

This book basically approaches you with the intention to extend your vocabulary and make you aware of all the flaws that our thinking contains, and I will lay out the key principles for my readers today. Don't be surprised if I quote some phrases from the book itself, it's very hard to explain some principles.

1: Two Systems

Daniel Khanemann explains our thinking in two systems of thought – system 1, which is fast, intuitive, and emotional, and System 2, which is slow, deliberate, and logical. We spent most of our time in System 1, it's your gut reaction or your intuition. System 2 is always in low-effort mode and is only used when needed.

For example, System 1 is the way of thinking you use when, recognizing a familiar face, jumping out of the way of an oncoming car or just making a snap judgment about a person's character.

On the other hand, System 2 comes to action when you consciously solve a difficult math problem or analyze a complex decision. Especially, system 2 uses a lot of glucose/energy when used a lot, that's why excessive thinking and problem-solving can be physically exhausting.

A general “law of least effort” applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action. In the economy of action, effort is a cost, and the acquisition of skill is driven by the balance of benefits and costs.

Laziness is built deep into our nature.

A fun fact I found in my notes is that our pupils are actually an indicator of mental effort:

“One of Hess’s findings especially captured my attention. He had noticed that the pupils are sensitive indicators of mental effort—they dilate substantially when people multiply two-digit numbers, and they dilate more if the problems are hard than if they are easy.”

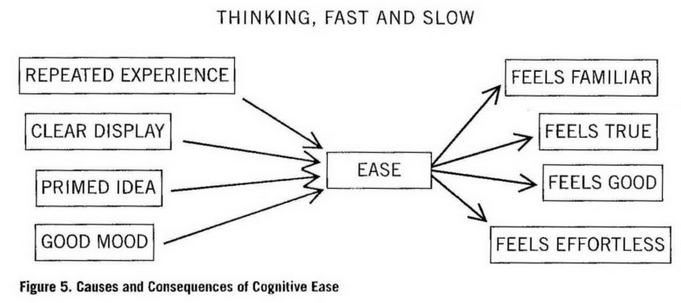

2: Cognitive Ease

Our brain literally despises using a lot of energy. It's so lazy that it always intends to take the easy route, that's where the principle of cognitive ease comes in. We experience this ease when our thinking is effortless and automatic. This comes with the effect that repetition makes something more believable for us, which makes sense. Back in the old days, we were much more likely to survive if we stayed in the familiar forest instead of exploring a new jungle. Whereas this also creates a vulnerability.

If we hear something over and over again, then it gets reinforced in our minds, and by that, the idea eventually feels true.

3: Priming

I found this principle to be very fascinating. So, external stimuli can influence us more than we think. It happens unconsciously, of course, but it can have some weird effects we don't even notice. For example, Daniel Khanemann tells us about a scenario where a study found out something interesting. There was a poll about increasing the funding of schools, and the polling station actually influenced the voting.

Our vote should not be affected by the location of the polling station, but it is. A study of voting patterns in precincts of Arizona in 2000 showed that the support for propositions to increase the funding of schools was significantly greater when the polling station was in a school than when it was in a nearby location.

Another example would be that simple priming effects of money actually influence us in antisocial ways:

Participants primed by money chose to stay much farther apart than their nonprimed peers (118 vs. 80 centimeters). Money-primed undergraduates also showed a greater preference for being alone.

You may not think that these findings relate to you, since they do not match your personal experience. However, your personal experience is mainly composed of the narrative that your conscious thinking process (System 2) creates about what's happening. Priming effects, which happen in the automatic and intuitive part of your brain (System 1), occur without you being aware of them.

4: The Halo effect

The Name of this principle implies its effect pretty well. It's the phenomenon that you judge an individual's overall character or abilities based on a single favorable characteristic or trait.

If you like the president’s politics, you probably like his voice and his appearance as well. The tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person—including things you have not observed—is known as the halo effect.

Or another example would be, that if you find someone attractive, successful or intelligent, you are more likely to attribute positive characteristics to that person in other areas. That is also one reason why first impressions are so vital.

It should be noted that Daniel Khanemann explains this cognitive bias as a consequence of the way our brains process information. We are wired to make quick judgments based on limited information, which can lead to systematic biases and errors in our thinking. Even better: as mentioned with cognitive ease, the consistency of the information is more important than the actual completeness. If many of your friends believe that a person is attractive, then you will also start to believe that and automatically draw biased conclusions about his abilities in other fields.

5: Framing Architecture

Information can be presented in different ways, and those perspectives evoke different emotions. Imagine this: you are in a hospital and got diagnosed with something. The doctor checks some papers, followed by this statement:

“The odds of survival one month after surgery are 90%”

Now, how did you feel after reading this sentence, maybe a bit unsettled?

Now imagine this:

“The chance of you dying within one month is 10%”

How do you feel now?

Those are the same statistics, but framed differently. Most patients probably find the second statement more unsettling, even though they are the same. It's the same as with Milk, it could be framed as “90% fat-free” or described as “10% fat”.

Well, perhaps now you realized how big this book actually is because I feel like I just scratched the surface. There are so many more facts and principles that are told about our thinking in that book. Though, it's difficult to get a lot out of this book:

"People who are taught surprising statistical facts about human behavior may be impressed to the point of telling their friends about what they have heard, but this does not mean that their understanding of the world has really changed. The test of learning psychology is whether your understanding of situations you encounter has changed, not whether you have learned a new fact. There is a deep gap between our thinking about statistics and our thinking about individual cases."

The book contained so much information that it literally forced me to find some efficient way to note it all, which I did. I already told you about the website I used, so maybe check out that other blog. You know, we already reached the 1250 words which is record length, so instead of boring you with more facts, just enjoy your Sunday ^^

I might make a part two, but for now, this will suffice. Have a lovely day!